The Waterfall methodology was once the dominant approach that informed the project life cycle and processes software development teams followed. A linear development model that unfolds in strict sequence, each phase of the Waterfall methodology’s life cycle begins when the previous ends.

- Analysis

- Design

- Implementation

- Testing

- Maintenance

The methodology’s name is a nod to the fact the traditional Waterfall model, unmodified, does not allow a software development team to return to previous phases of the life cycle once they are completed – the project, like a waterfall, flows in one direction only.

Until the turn of the present century and the release of the Agile Manifesto in 2001, which has since seen an array of Agile methodology software development frameworks from Scrum to Adaptive Software Development (ASD) dominate, most significant software development projects followed the Waterfall methodology.

For example, in 1985 the United States Department of Defense formalised standards every software development company or specialist contracted to work on DoD projects must follow. These requirements were centred around a non-negotiable five-phase Waterfall life cycle of:

- Requirements analysis

- Preliminary design

- Detailed design

- Coding and unit testing

- Integration and testing

Can We Help You With Your Next Software Development Project?

Flexible models to fit your needs!

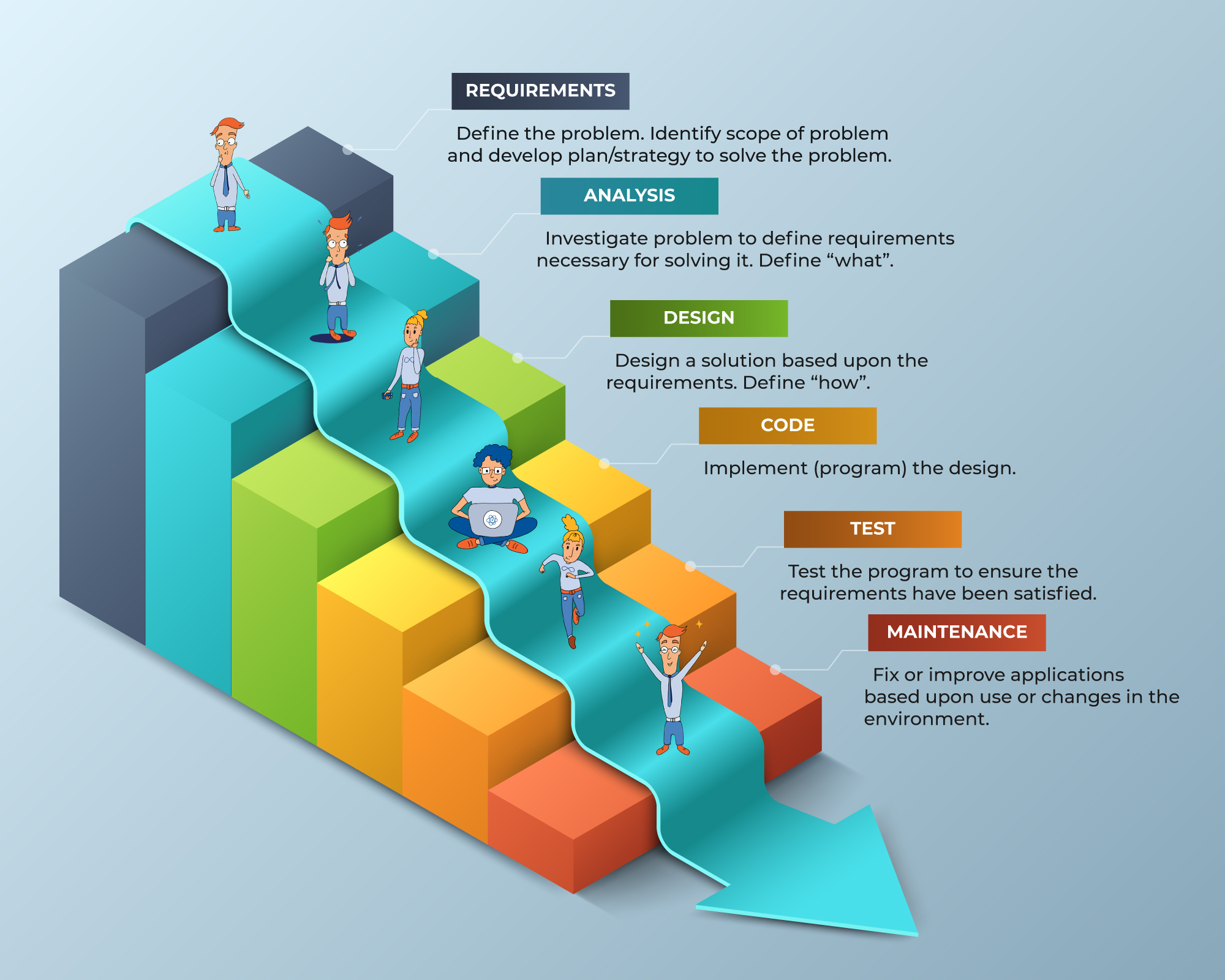

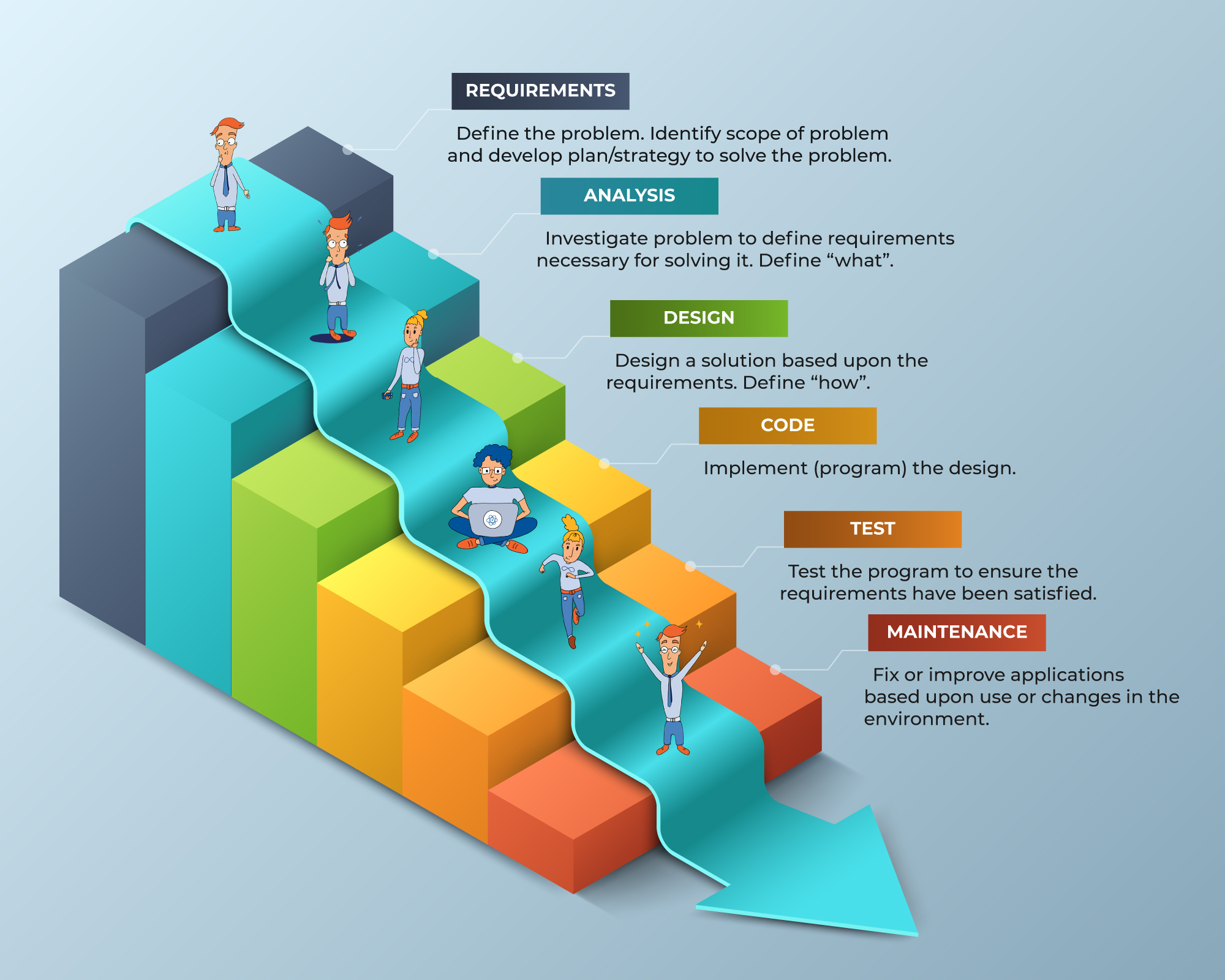

The phases of Waterfall-model software development

Different write-ups of the Waterfall model come with slight variations on the methodology’s life cycle phases. The simplest Waterfall model defines just 4 main stages:

- Requirements analysis

- Design

- Implementation

- Testing

But most Waterfall model diagrams and explanations add another stage or two. The DoD’s Waterfall model, for example, had two design phases – preliminary and detailed design. In the software development context ‘deployment’ and ‘maintenance’ phases are also often included.

Requirements analysis

The linear nature of the Waterfall methodology gives additional significance to this first stage in its life cycle. All requirements of the final software product’s utility and features have to be gathered here.

Once the requirements analysis stage is completed the software development team should have all the information needed to complete the project without any, or minimal, further involvement from whoever has contracted or otherwise. initiated the project.

Design

The design phase is often divided into two subphases – logical (or preliminary) design and physical (or detailed) design. The logical or preliminary design phase involves putting all possible solutions on the table and analysing their strengths and weaknesses within the context.

Once theoretical ideas have been assessed and decisions taken on which to go with, the physical or detailed design phase is when they are documented and detailed as concrete specifications.

Implementation/Coding

The rump of the project – when software developers write and assemble the actual code that turns the specifications detailed in the design phase into a functioning software system.

Testing

When the implantation phase has been fully completed, manual software testers (who might be supported by automated testing tools in contemporary software development projects) have to make sure every component of the software system works as intended, both autonomously and across any dependencies.

Testers will use documentation created at the design phase, user personas and user journey scenarios to run as many test cases as possible in the attempt to uncover any bugs that need to be fixed before deployment.

Deployment

When the software system has been tested and approved for release, a copy must be transferred from the software development environment and released in the live staging environment from which users will be able to access and use it. This stage is called deployment.

Team members responsible for deployment should be aware of any differences between the software development and live server environments and make any adjustments needed for the software to run the same way in both.

Maintenance

In the maintenance phase, the software is in use and the primary job is now to keep it available and running smoothly as well as fixing any bugs reported by users that may have been missed during the testing phase.

K&C - Creating Beautiful Technology Solutions For 20+ Years . Can We Be Your Competitive Edge?

Drop us a line to discuss your needs or next project

The Waterfall methodology’s history – criticised by its creator

The earliest documented use of the term ‘Waterfall’ to describe a software development methodology are believed to be academic papers published from 1976 on. These references to the Waterfall model used a diagram first used in an article written by the American computer scientist Winston Walker Royce.

Royce was director of the Lockheed Technology Centre in Austin Texas and widely considered a pioneer of the software development field. The article presented a diagram of the five sequential phases of what subsequently become known as the Waterfall model, though Royce himself didn’t use the term.

In fact, Royce wasn’t advocating what became the Waterfall methodology at all but criticising it as flawed, describing it as “risky and invites failure”. The main body of the article outlined five additional phases he felt would compensate for the simplified original life cycle’s deficiencies to “eliminate most of the development risks”.

Royce’s more sophisticated Waterfall model emphasised the need to involve the user, test throughout the process and write extensive documentation at various stages. It never gained any real traction but the stripped-back original diagram he considered to “invite failure” did.

It became the methodology of choice for strategically important enterprise-level software development projects such as CRM Systems, Supply Chain Management Systems and, as mentioned, the methodology key U.S. governmental departments like the DoD demanded software development contractors work to.

The fall of an empire – the Waterfall model’s weaknesses were exposed by advances in software development

As software systems became larger and more complex in the 1980s and 1990s, the weaknesses in the traditional Waterfall model highlighted by Royce were often badly exposed. Large organisations like government departments, banks and blue-chip enterprises across a wide spectrum of sectors were by now embarking on ambitious software development projects intended to leverage new technology to make them more efficient.

There are countless stories of hugely expensive software development projects that turned out to be white elephants. The most common reasons why huge software projects have historically failed are:

- Take so long to develop they are technologically outdated by the time they are released.

- Take so long to develop the market changes before they are released.

- Scope too large for the project management to effectively handle.

- Mistaken presumptions and failure to fully understand user needs at the requirements analysis phase mean the completed software product is not fit for purpose.

- The extent of bugs and other problems discovered at the testing phase so great fixing them is not considered commercially viable.

The Waterfall methodology’s strict linear model played right into the hands of each one of those risks. The requirements decided on at the beginning were delivered with laser focus. Which is fine as long as the requirements set at the beginning of the project are bang on the money.

But as software systems became broader in scope and more complex as they tackled bigger problems, more variables were introduced. More variables meant more chance of wrong assumptions and other mistakes being made at the requirements analysis phase.

With a Waterfall approach to the project management of software development projects, those wrong assumptions and mistakes are often not discovered until the end. The bigger and more expensive the project, the higher the exposure to failure.

That resulted in a lot of spectacular and high profile failures for the Waterfall methodology and its reputation took a battering. More user-focused variations on the standard methodology that introduced testing earlier in the life cycle, like the V-model evolution, attempted to compensate for weaknesses and make the Waterfall approach more flexible.

Agile succeeded Waterfall as the dominant approach to software development

As the conveyor belt of costly, sometimes spectacularly so, white elephant projects continuously presented evidence of the Waterfall methodology’s ill-fit to the contemporary software development landscape, an alternative was rapidly gathering momentum.

The Agile methodology’s traction in replacing Waterfall was helped along by almost evangelical faith among the pre-social media influencers of Silicon Valley’s tech scene. The California influence was apparent in the enthusiastic, sometimes dogmatic, introduction of Agile frameworks like Scrum which prescribed strict rituals including ‘daily stand-ups’ and introduced team role names like ‘Scrum master’.

But despite some of the ritual sitting uncomfortably as ‘a little too California’, the Agile methodology and frameworks from Scrum to SAFe (scaled agile framework) and SoS (scrum of scrums) did represent tangible advantages for contemporary software development project management.

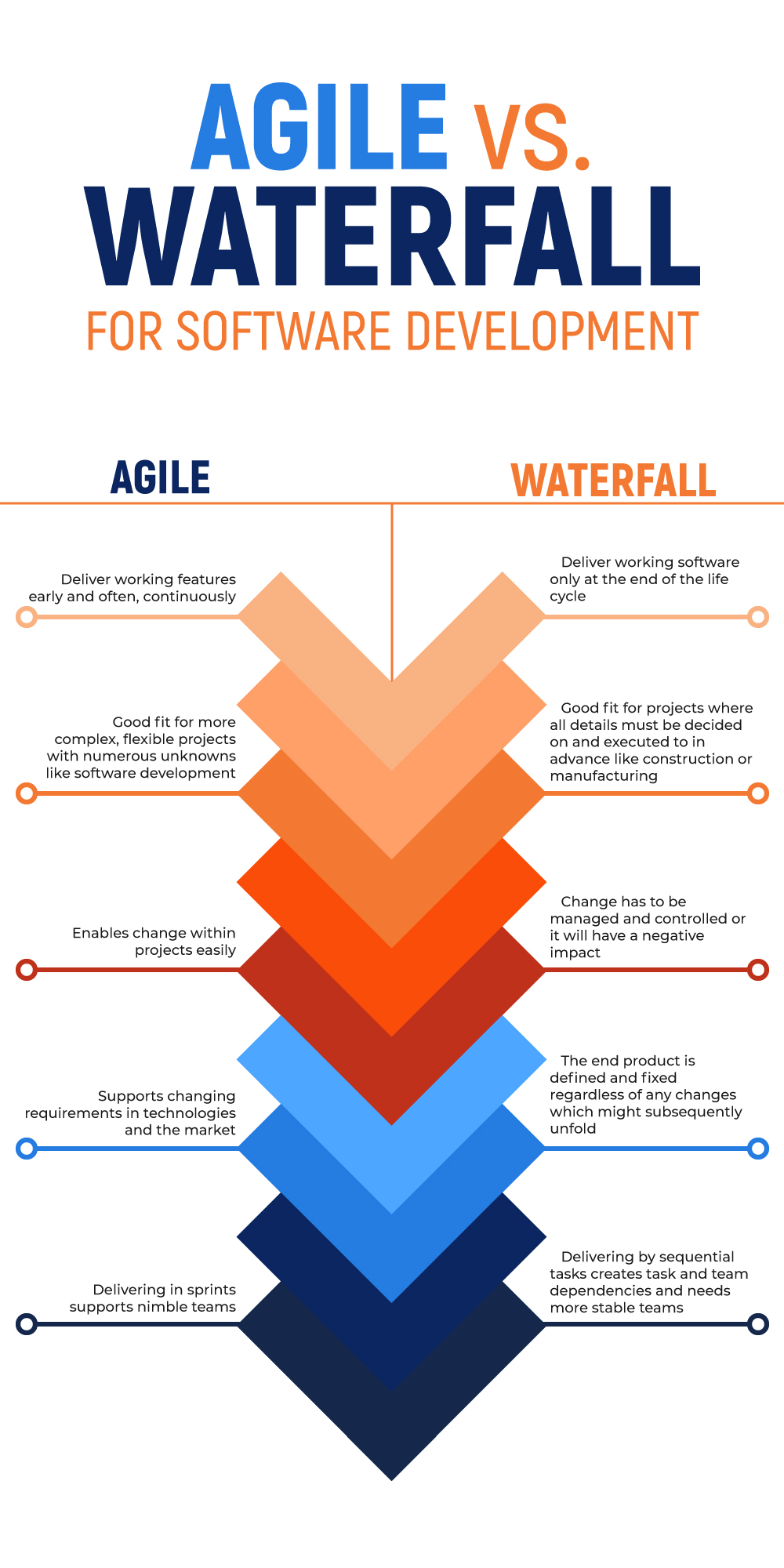

The core of the Agile approach to software development is that it is iterative and flexible to changing requirements. The methodology starts with the assumption that for many software development projects it is difficult, often unrealistic, to gather full requirements at the start of the project. Even with the best of intentions and diligent attention to detail, there will be mistaken assumptions that could, in the worst case scenario, lead to a white elephant software product and in less extreme cases mean the product is not as popular with users as it could be.

Different Agile frameworks vary in their exact life cycle phases, detail and prescribed steps. But they all start with prioritising the development and launch of a working MVP that represents the least amount of features possible while still adding value for users. The MVP is then iterated upon based on user behaviour and feedback and often grows considerably in scope and complexity over time.

The iterative loop-back approach of Agile goes a long way to neutralising the risk of significant time and money being spent developing a software product that turns out, for whatever reason, to not be fit for purpose or competitive to alternative products. Any major issue should be quickly identifiable and then adjusted for without having to pull apart a large software product of complex dependencies built on the foundation of mistaken assumptions.

Is the Waterfall methodology ever still a good approach to software development?

Like any methodology, Waterfall has its strengths and weaknesses. It didn’t establish itself as the dominant software development approach for close to two decades by bringing nothing to the table.

Waterfall’s strengths and weaknesses are both a product of its simplicity and linearity. A Waterfall approach can make sense for smaller projects where the requirements are crystal clear, required resources made fully available and there is a tight, imminent release deadline.

Waterfall’s strengths are a good fit for software development projects where:

- Requirements are clear, fixed and free of any ambiguity

- Product definition is stable

- The technology stack is defined and fully understood

- Financial and expertise resources are made fully available

- The project’s timeline is short

Waterfall’s weaknesses mean it is not a good fit for software development projects where:

- There is more than a very low level of risk requirements and scope may change as assumptions become better informed

- Mid to high level of complexity

- Mid to long timeframe for implementation

- Product development will be an ongoing process

- Any other variable may change before the finished software product is released

The reality is that in 2021 there are very few software development projects that meet the criteria that play to Waterfall’s strengths while avoiding those that expose its weaknesses. They do exist, which means the Waterfall methodology is not entirely irrelevant in 2021. But the rarity of the circumstances that would combine to favour Waterfall is such that it is largely now seen as a legacy methodology from a previous era of software development.

When does IT Outsourcing work?

(And when doesn’t it?)